Developing novel, noninvasive solutions to address the needs of clinicians and patients alike.

Along West Peltason Drive sits an unassuming red-roofed building otherwise known as the Beckman Laser Institute & Medical Clinic (BLIMC). Inside, through a maze of hallways, doorways and stairwells, is the office of Dr. Petra Wilder-Smith, director of dentistry at the BLIMC and professor of surgery at the UCI School of Medicine. In her office and in labs throughout the facility, Wilder-Smith studies oral cancer and devises novel, noninvasive optical techniques for medical purposes.

A Better Way

After finishing high school at 16, Wilder-Smith faced a question many are familiar with: What am I going to do next? A few visits to a friend who was attending dental school in London at Guy’s Hospital was all she needed to convince herself to do the same. Despite not knowing much about dentistry beyond that Guy’s Hospital was the best dental school at the time, she applied and was accepted into the five-year program. The first two years were “marvelous,” as she puts it, studying subjects like physiology, pharmacology and biochemistry. When the third year came around and pre-dental clinics began, she soon realized that dentistry was not for her.

It began with a patient who exhibited nonvisual symptoms of oral cancer. After following her supervisor’s instruction to take multiple biopsies which all came back as negative for oral cancer, Wilder-Smith thought her work with the patient was complete. Her supervisor informed her otherwise, as more biopsies were needed to discover the cause of the symptoms. Much to the patient’s dismay, Wilder-Smith took a few more biopsies, one of which eventually came back positive for pre-malignant oral cancer. As is the case with other patients in this scenario, the patient was instructed to return every six months for biopsies to monitor her condition. And just like nearly 80 percent of patients over a three-year period who receive these instructions – according to Wilder-Smith – her patient did not return.

And so began Wilder-Smith’s journey, summed up by her statement of displeasure with the status quo: “There has to be a better way.”

Having liked oral medicine, yet concerned about the way it was being approached clinically, Wilder-Smith went to her oral medicine professor and asked him to be her mentor.

During her final exam, Wilder-Smith told her examiner, “This is the last filling I’m ever going to do in my whole life.” And it was.

Sights Set

With her newfound mission to study oral medicine and oral cancer, Wilder-Smith went to the University of Bern in Switzerland where she received her doctorate of dental medicine, and then to Heidelberg University in Germany where she received a specialty license in oral medicine.

But something was still amiss.

“Why are we so bad at this,” Wilder-Smith recalled asking herself. “You can’t detect or diagnose it visually. If you look at it, you might as well toss a coin; you don’t know if it’s an ulcer, a burn, an autoimmune thing or cancer.”

And with biopsies as the only way to diagnose oral cancer, clinicians find it hard to keep patients returning when they find out they need to be biopsied regularly to monitor their condition.

“No one is going to let you take a chunk out of their mouth every six months; it looks horrible and it hurts,” said Wilder-Smith.

After joining the BLIMC in the early ’90s, Wilder-Smith knew that a noninvasive approach was the best way to ensure better oral cancer management. She took it upon herself to understand the basic science behind noninvasive techniques by attending Aachen University in Germany to complete a Ph.D. program in biomedical imaging.

Filling the Gaps

Wilder-Smith’s work at the BLIMC currently focuses on all the problems associated with oral cancer, from determining a patient’s risk level and monitoring those at risk, to using advanced imaging techniques to identify cancerous tissue at the molecular level.

According to Wilder-Smith, the detection and recurrence rates of primary oral cancers are horrendous, with oral cancer being the only major cancer whose outcomes have not improved in the last generation. Because of this, a large part of her work revolves around devising ways to provide the most at-risk populations with screening and monitoring.

Compounded by risk factors like dietary insufficiencies and smoking and drinking habits, the people who need the most help are often those who have the least access to medical treatment. Her work with aid groups has taken her to rural parts of India, Turkey and China where access to medical care is scarce. These experiences have shaped her and her team’s understanding of the barriers faced by people in low-resource environments.

Based on the information gathered in these rural areas, Wilder-Smith and Dr. Rongguang Liang, professor at the College of Optical Sciences at the University of Arizona, worked together to design and create oral probes that attach to smartphones, allowing anyone who can operate a smartphone to take images of the oral cavity. Once the photos are collected, the accompanying smartphone application runs a sophisticated image-processing algorithm to make informed analyses on whether or not the photographed tissue is at risk. From there, the images are wirelessly transmitted to a remote specialist who can diagnose and provide a treatment plan depending on the severity of the patient’s case. In India, with help from an Indian philanthropic organization, 400 community workers participate in ongoing projects to bring oral cancer screenings to low-resource areas.

Many of these community workers are utilizing these devices and providing regular feedback on how to further improve them.

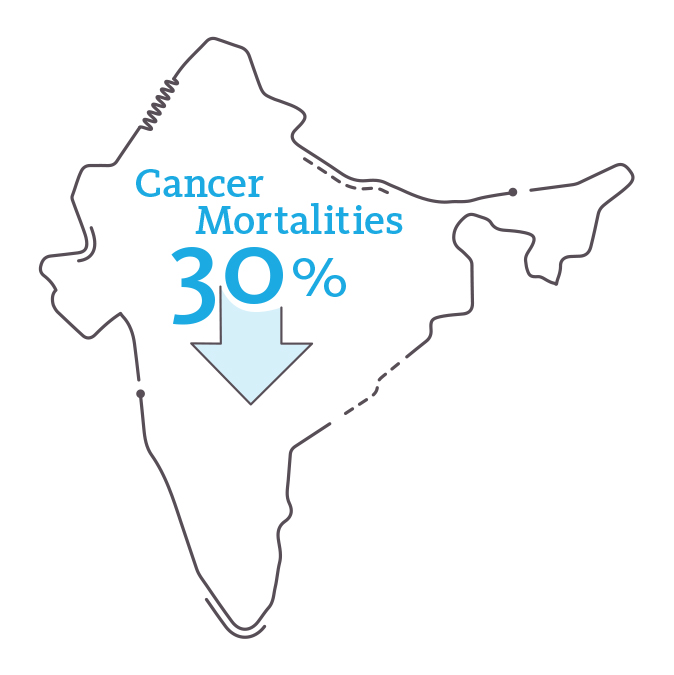

Even providing access to screenings can offer substantial improvements, as Wilder-Smith has seen oral cancer mortalities decrease by 30 percent in the parts of India where these projects are underway. Additionally, outcomes there have improved because oral cancer is caught at earlier stages, which requires less-invasive surgery.

New Technologies

Her pursuits do not stop at designing portable oral cancer screening devices for low-resource populations in the developing world. Wilder-Smith also works with engineers to develop advanced imaging to map cancerous tissues in the mouth. The problem the team aims to solve is this:

How do you determine where a cancerous lesion begins and ends when that information can only be seen at the molecular level?

The current surgical approach is to identify where the microscopic edge – or margins – of the lesion is, and then remove one and a half centimeters around the lesion in three dimensions in hopes of removing all of the cancerous tissue. Remove too little and the cancer might remain; remove too much and a patient might have problems swallowing, eating or talking.

“There’s no way we should be excising with such wide margins,” said Wilder-Smith. “My goal is to use our highly sophisticated imaging tools to map the molecular risk so that we can tell the surgeon, first when they plan the surgery, and then intraoperatively, how close they can keep the excision to the tumor margins and still keep a minimal risk of recurrence in the patient.”

This technique aims to improve outcomes for patients, could reduce the number of surgeries required and provide patients with a higher quality of life post-surgery.

Another area Wilder-Smith focuses on is entirely new to her: starting a company. Based to a large extent on their patents created while at the BLIMC, Wilder-Smith and her colleague Cherie Wink, assistant research specialist, think about some of the biggest challenges clinicians face and try to fix them, mainly through improving on medical instruments.

One such improvement they are working on is finding innovative ways of reducing airborne transmission of disease from devices – like ultrasonic scalers, craniotomes and bone saws – that are known to send tiny droplets of biological material into the air. By eliminating bacteria in the droplets before they go airborne, the risk of infecting patients hours, or even days, after their unintended release can be reduced.

Their new experiences of licensing patents and starting a company has led them to UCI Applied Innovation, where they receive licensing guidance from Doug Crawford, senior licensing officer, and business consulting from Molly Schmid of the Small Business Development Center (SBDC) @ UCI Applied Innovation.

“What I’m most excited about is learning how to be a startup; learning how startups work, learning how business works, learning how intellectual property and technical know-how translates into building a viable business, and all of the variables that go into that,” said Wilder-Smith. “I’ve never done it and I love it.”

Wilder-Smith and Wink build prototypes based on their patents with the intention of licensing and developing them with large dental or medical companies.

The UCI Difference

What makes her work especially gratifying, she says, is not only the interdisciplinary structure of the BLIMC, but also the collegial nature of the university as a whole. Whether her projects need engineering, computer science, materials science or even artificial intelligence support, UCI faculty are just a phone call away and always willing to lend a hand.

“I’ve never had someone say, ‘no I don’t have time,’” said Wilder-Smith. “It’s always, ‘cool, yeah, let’s do this.’ I think UCI is very unusual in that regard. I think we’re very fortunate.”

Together, Wilder-Smith, her colleagues and UCI faculty at large are making strides toward the BLIMC’s vision of moving innovative technologies from “benchtop to bedside” to improve lives in all communities, in the U.S. and abroad.